Noah & the Flood (Genesis 6-9)

You know the story. God sees His creation and that it’s a disaster. Genesis 6 begins with human beings being beyond dastardly. Verse 5: “the people on earth were very wicked… all the imaginings of their hearts were always of evil only.”

Its not just humans that are so dastardly, though. The whole earth is and all living beings are, according to verses 11 and 12: “The earth was corrupt before God, the earth was filled with violence. God saw the earth, and, yes, it was corrupt; for all living beings had corrupted their ways on the earth.”

As if to reiterate the dark reality, God communicates to Noah what his divine eyes sees: “The end of all living beings has come before me, for because of them the earth is filled with violence.”

Violence is mentioned twice in chapter 6. Cain tapped into a kind of

black hole for earthly existence. Cain’s violence begat more violence. No

surprise. That’s what violence does. To use lingo from Star Wars again, Cain’s

act, his full and complete emersion in the dark side, creates an irredeemable disturbance

in the Force. Everything in the wake of Cain’s fratricide, in the wake of that violent turn, violence marks the whole of creation and human life.

Another recurring theme in our story is God’s regret. The story begins and ends with regret. We see God’s regret at the very beginning of the Noah narrative. Verse 6 points to it: “Adonai regretted that he had made humankind on the earth; it grieved his heart.” God regrets and grieves the harsh reality of creation. Here, too, God – Adonai – voices his regret to Noah. Verse 7: “I regret that I ever made them.” (As for the end of regret, we must wait numerous paragrahphs.)

From God's regret toward his creation, you know the rest of the story. God commands

that Noah build a huge ark and gives him exact dimensions (vs. 14-16). He

commands Noah to fill the ark with creatures of every kind, male and female for

procreation’s sake (vs. 20-21). God commands food be brought and stored (v.

21).

Why? Verse 17 gives the details to verses 6 and 13: “I

myself will bring the flood of water over the earth to destroy from under

heaven every living thing that breathes; everything on earth will be destroyed.”

In chapter 7, verse 4, God repeats his plan in case you somehow missed it: “ I

will wipe out every living thing that I have made from the face of the earth.”

Only Noah and his family will be saved (v. 18).

God follows through on his plan. Genesis 7:11-12 and 17-24

gives the details. Forty days and forty nights of unrelenting rain, floods, and

death with only one family of every kind surviving.

Horrifyingly to me, the story of Noah is often offered up as the perfect Bible story for children. It is often on the cover of Children’s Bibles. It is the subject of children’s songs and games.

Now, the animals going

two by two into a big boat indeed makes nice, kid-friendly pictures. But the

text itself is the farthest thing from a children’s story. It is harsh filled

with violence, regret, grief.

Basically, the narrative portrays God annihilating all

humans but Noah and his family and all animals but a couple of each species.

The rest are drowned by floods. The story basically amounts to God committing

mass genocide on a global scale.

Despite being read to kids all the time and for millennia, the

story is not at all for tender ears.

Christians everywhere teach their kids that God is Love. But

how can a God who is Love act in this way? The cognitive dissonance is paralyzing.

What are we do with the Noah narrative? Can we come up with

a nonviolent reading of this story, one of the most brutal in the Bible?

The answer is yes.

To do so, we must first understand the context of the

narrative. The story doesn’t develop out of thin air. It derives from a specific

time and place, and this context tells us a lot and gives a deeper appreciation

of the narrative.

I begin by making clear that the story of Noah and the Flood is not an original story. The Noah story is a kind of remake movie.

The old Japanese samurai movie called The Seven Samurai came out in 1954. Six years later, in 1960, an American Western remake called The Magnificent Seven hit the big screens. We have a similar example with the Noah and the Flood story.

The original story of the Flood was set in

Ancient Mesopotamia, in Babylon to be specific, and told in the Epic

of Gilgamesh. That tale, the Flood of Gilgamesh, was later retold in a different place and a different

culture - in ancient Israel. We know it as the story of Noah and the Flood.

The Flood of Gilgamesh story dates back to nearly 3,000 BC. It has the same basic storyline albeit in a polytheistic religious setting.

In the older Babylonian story, there is a god, Enlil his

name, who becomes really angry at his people because they are so noisy that

they interrupt Enlil’s sleep. Enlil decides to rid himself of every single one

of them.

As with God-Adonai in the Noah story, Enlil opens the skies

and causes it to rain for forty days and forty nights, creating a Flood that kills

millions.

However, the flood fails to drown everyone. A few people escape.

The god, Enlil, is disappointed and annoyed at this. But unhindered, he goes on attempting to get rid of the rest, and eventually succeeds

The Noah story seems to detail the same catastrophic weather event. Both the Flood of Gilgamesh and the Noah story are looking at the same historical event. But the latter gives us a different slant in its telling of the Flood. The key differences are striking.

First of all, God is not angry because a noisy crowd interrupts

a time of divine beauty sleep. In the Noah story, there is real injustice

described. God’s people are off their rockers. The whole of creation is off its

rocker. And violence is at the heart of it all.

Simply put, the creation God deemed as good in Genesis 1 is

not functioning that way. Creation, beginning with Adam and Even and then Cain

and Able, has gone to the dark side and grown unjust and unrighteous. This is

the impetus for God wiping the canvas clean and recreating again.

Now, is this to be read literally? Did Adonai really annihilate millions of

people? Of course not. However, the point is clear: sometimes a people lose

their way so badly that all that can be done is to figuratively wipe the slate

clean and begin anew

We have examples of this wiping the slate clean and starting

again in history. The American and French Revolutions can be seen as great

examples of this. Or maybe even the Civil War or the Civil Rights Movement. The

war against Nazism is another example.

Things became untenable. A reset becomes necessary. And

something revolutionary, which literally means a drastic turn, must occur for

that reset to take effect.

There are good ways and bad ways of making revolution

happen. In the case of God’s choice of revolution in the Noah and the Flood

story, where God wipes out a whole globe, God comes to see that his choice was

the wrong one.

The Noah narrative ends with Noah worshipping God with a

sacrifice and God replying with a promise. Chapter 8, verses 21 and 22 are

quite powerful:

“Adonai smelled the sweet aroma, and Adonai said

in his heart, ‘I will never again curse the ground because of humankind, since

the imaginings of a person’s heart are evil from his youth; nor will I ever

again destroy all living things, as I have done. 22 So

long as the earth exists, sowing time and harvest, cold and heat, summer and

winter, and day and night will not cease.’”

In this description, we see a couple other big differences

between it and the original Flood of Gilgamesh story. In the Noah story, God

still maintains some hope for a big turnaround in his creation. This is

profoundly seen in God’s covenant in the wake of the Flood (9:1-17). In the

Babylonian story, Enlil wants to annihilate absolutely everyone so he can get

some sleep.

Maybe more importantly, in the Noah story, after the flood

has done its deed, God reflects on it all and seems to regret his decision. He

then promises to never act so harshly and drastically again. This is where we

get the lovely image of the rainbow as representative of God’s promise of grace

here on out (9:13-16).

In the Babylonian story, the only regret Enlil has is that

his plan didn’t work, that some escaped his wrath. Instead of vowing against

such violent actions again, the god vows to finish the job.

So, we can safely say, the God portrayed in Genesis 5 is one

that marks a step forward in human religion’s view of God. This God has some

sense of justice and is not fickle. This God seeks to save the just. This God

is reflective and even regretful when He sees the devastation sown. This God

promises to never fall into such depth of despair and wrath again. This God

re-creates the world anew in the wake of his regret.

It is hard for some of us to look at God in the Bible as a

being that is evolving and growing and capable of a change of heart. But this

is the God we see, especially in Genesis. We will later see this in God and his

intimate friendship with Moses and how that relationship often moves God to

make more compassionate decisions.

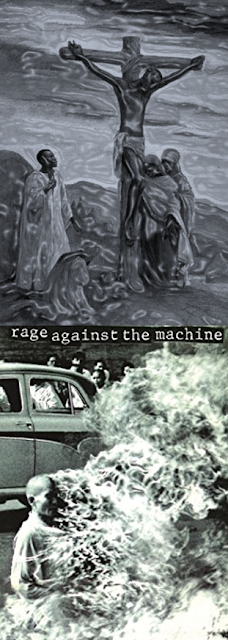

And of course, we will eventually get to Jesus of Nazareth

and the Christian revolution. Jesus will overturn the law of retributive

justice found in 9:6 – “whoever sheds human blood, by a human being will his

own blood be shed” – with the way of nonviolence and forgiveness (see the

Sermon on the Mount).

Lastly, as we muddle through the election of our country’s leader, we see in God pre-Flood a being, a being a little too comfortable with and casual about his power. We see a leader that lacks a certain degree of self-reflection and self-awareness. You know that saying, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” We see this in the being of God.

But after the Flood, God learns. God comes to terms with his own power. Post-flood, there’s a certain degree of self-reflection and self-awareness in God.

And what does God do after this promise to assure absolute power

doesn’t corrupt? God goes about sharing some power with a people. God chooses

Abraham to be his conduit for a new nation, the nation of Israel. Abraham

becomes the first patriarch in a line of patriarchs whom God partners with to

forge and foster a nation devoted to God’s work of justice and equality.

This is to say, the dangerous use of power and the

destruction that resulted in the Flood teaches God the necessity of sharing

power in relationship with others.

The larger lesson that we see is God’s vow to forsake unjust violence in his dealing with creation.

Instead of wrath, now God chooses love.

The rainbow God represents God’s peace-covenant, God’s promise to now deal with the world in life-affirming ways.There's even more to that rainbow promise.

That promise is none other that Christ.

The wood of the ark will become the wood of the cross. And Christ, the embodiment of selfless love on the cross, will defeat human wrath, the sin of violence, hate, and death, and rise victorious. God's wrath is exchanged for God's love, the only antidote for human violence. The promise is Christ. The rainbow symbolizes Christ. Divine destruction is now divine compassion, the only way forward.

This was a huge step forward in understanding religious truth. Angry, wrathful, bloodthirsty, warpath gods were seen everywhere and presumed as a part of the way things were. The God presented in the Noah story, however, represents a radical, revolutionary turn. The Noah story, as hard it is in our modern context to read and be okay with, points to a radically new view of God and religion. In the Noah story we see a God forsaking the way of violence and promising a way of peace.

Comments

Post a Comment