Buddhism & Christianity: Sin, Salvation, Overlap

Let’s move on to two other questions:

For Buddhism and Christianity:

- Are humans fundamentally good?

- What goes wrong?

For Christianity, as we know, humans are created in God’s

image, enlivened by the Spirit of God. Life in Eden marks the original plan for

human beings. Unity between humanity and God and balance in creation was the

reality in the beginning. But with Adam and Eve’s fateful decisions, a shift

occurs. Christians have deemed it the Fall.

A fall into what? Into the reality of sin. From the bite of

the bitter fruit thereafter, sin marks human life.

There are differences of opinion on how deep the effect of

Adam and Eve’s sin goes. The line of Augustine, which crosses the

Catholic-Protestant divide into Luther, and Calvin, says sin

runs very deep, arguing that the guilt for the original sin of Adam and Eve is

passed on to every human born thereafter. Even infants carry the guilt of

original sin, and thus deserve the consequence of judgment and punishment sin carries.

The line of the Cappadocian fathers in the Eastern church

have a more positive view of things, arguing that humans don’t inherit Adam and

Eve’s guilt for sin, but do inherit a propensity to choose sin. I use the

difference between inheriting cancer at birth (Augustine) versus inheriting a cancer gene, meaning

you have a predisposition to develop cancer (Cappadocians).

So, what does this mean? Does Christianity say we are good

by nature? The Augustine line is a clear no, we are sinful by nature. The Cappadocian

fathers would say, deep down, in theory, we still carry the image of Good in us. But in practice, because of sin, we are naturally prone to sin. Though the image of God is still real

within each of us, the propensity to sin thanks to Adam is real as well. If

we’re good by nature, we’re also prone to sin by nature.

What about Buddhism? Are we good by nature according to the

Buddhist teaching?

The Buddhist answer resembles the Eastern Orthodox answer

though the language is very different. Yes, in theory we’re good, but in

practice, we are prone to sin.

Like Christianity, there are two lines of thinking that

slightly vary. The first line is the Theravada line. Mainstream, traditional

Buddhism (Theravada) “believes that ordinary beings in the cycle of rebirth are already

born in a state of delusion and thirst, i.e., with quasi-‘sinful’ inclination.”

However, for humans, there's the potential to, through the Buddha’s help, improve

on your state and be reborn into a better life.

The second line is the Mahayana line. Mahayana develops a more positive view of humanity. Not only is there potential to improve on your state, the potential to in this life become an enlightened being is there within humans.

Mahayana by the 4th century CE develops an even more positive view of things.

A school of Mahayana comes to teach that not only is the potential for

enlightenment, aka Buddhahood, within us, Buddhahood itself is already a reality within

us. It is latent, but it is real. Each of us possess what is called Buddha-Nature.

Our true selves are enlightened. We simply need to actualize our true selves.

This brings up something I mentioned last week. True Self. Zen

Buddhism which is a later form of Buddhism that develops in China around 7th century CE. Zen develops a notion of True Self, which is another name for Dharmakaya.

Remember we talked about how Dharmakaya, body of truth Buddha, is as close to the

Christian God that Buddhism gets. Well, True Self is akin to God. As for us, we

are born as carriers of that True Self within us. As we live our lives, that True Self becomes sullied and covered with dirt and we live as human selves and

often in a selfish way. In the process, we distance ourselves from who we truly

are. We distance ourselves from the True Self within us. The idea of Zen practice is to get actualize

True Self, which is our original nature.

So again, Buddhism runs the gamut. Theravada says there’s potential

in us to improve our state in the next life and even eventually become a Buddha

in lives to come. Mahayana in its most developed form says, we each are born

with Buddha-nature waiting to be actualized so that we become Buddhas in actuality, not

in just theory.

That brings us to the question, what’s wrong with us? What’s

the problem? Why don’t we realize our potential and actualize what is latent

within us, either it be God's image or Buddha-nature?

Christianity says sin, which means separation from God.

Buddhism asserts something similar, albeit in different language. Remember the

2nd noble truth - we suffer because we grasp onto and crave things

that in the end are impermanent and will never satisfy. Tied to our grasping

and craving is our incorrect view of the world. We see our selves first and

foremost and everything else as secondary. This kind of ignorance and arrogance

along with our built in grasping onto and craving after things, whether it be

wealth, sex, fame, etc., taken together looks like the Christian notion of sin.

We grasp and grovel for worldly things, out of the ignorant idea that this me is an island and must come first.

Put another way, basic Buddhism says we suffer because we’re

distant and separated from the truth of interdependence – the truth that we’re all in

this together and rise and fall together - and instead choose to live the way

of selfishness.

Christianity would say we’re distant and separated from God but

instead live the way of sin, and so we suffer.

A lot of overlap there, right?

Okay, what is salvation?

In the first session, we discussed what salvation looks like

in basic Buddhism. Salvation amounts to following the Eightfold Path.

Right view and thinking; Right speech, action, and livelihood; Right resolve, mindfulness, and meditation.

This amounts to trusting the Buddha and the Buddha’s teaching

and living according to that truth. From this, suffering, craving, ignorance,

selfishness is overcome and we live a liberated life.

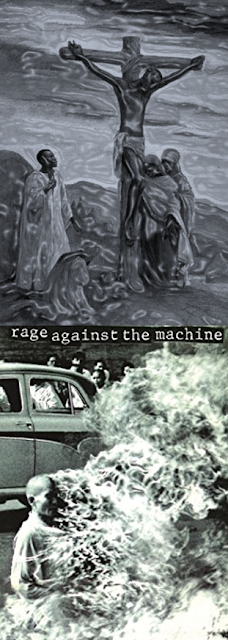

In Christianity, we know what salvation is. Faith in Christ

and in his work of forgiveness and redemption on the cross, and a following of

Christ and a living of his way means a saved life.

Now, in both religious traditions, there developed a radical

view that said humans are so far gone that we cannot rely on good deeds in the

process of salvation. Only grace can save us. Works are meaningless.

In Christianity, we see this in Luther especially. Sola gratia and sola fide – by grace alone and by faith alone. Only grace and our reliance upon (i.e., faith in) that grace can save. The sinfulness of humanity rules out any human effectiveness in the work of salvation.

In Buddhism, we see this same idea in Pure Land Buddhism,

namely the Shin Buddhism of a Buddhist figure named Shinran of Japan in the 12th century CE. Only Grace

found in Other Power and our reliance upon that Other Power and it’s grace can

save. The sinfulness of humanity in this age rules out effectiveness in human self

power in the work of salvation.

Lest we think Shinran is stealing from Luthernaism, Shinran

predates Luther by some 400 years.

Fast forward some 200 years, to the 18th century, and to a man named John Wesley, founder of Methodism. Wesley believed Luther was too quick to give up on the importance of sanctification in the salvation process. Yes, salvation in Christ means we’re made right, we’re justified, before God. But how do we know this being made right, this justification, is real? How do we know salvation itself is real? Well, Wesley preached sanctification.

If salvation really took, Christians will

naturally seek to live a holy life, a sanctified life. Without sanctification, our justification,

and our salvation as a whole, should be in doubt. For salvation relies on both

justification, us being made right before God, and sanctification, us being

made holy.

Well, some 600 year before, in the 12th century, Wesley, a Korean Zen monk named Jinul

taught something similar. He taught that sudden enlightenment is crucial to

living the way of the Buddha. Sudden enlightenment amounts to a sudden glimpse

into the truth of the Buddha and that the Buddha is right here, right now, within

us, connecting us to all in the universe.

We might see Sudden Enlightenment as parallel to the initial moment

of Christian salvation where we really see who Christ is and all he’s done, and spiritually fall at his feet as if he was right in front of us.

But Jinul said sudden enlightenment is not enough. We need

gradual cultivation.

We might realize the Buddha is within us, and we might realize that the truth of interdependence means we’re connected to everything else in the universe. But we must in turn actualize that truth by cultivating ourselves, living like the Buddha and living in accordance with our connection to other things in the universe.

If I know I’m connected to you, that we are related somehow, that you are my brother or sister in the Lord, I will treat you with love and kindness, as I love and am kind to myself.

Comments

Post a Comment