Beautiful Day

A Sermon by Don Erickson

delivered at St. Paul's Universalist Church, Little Falls, NY

Easter Day, March 31, 2013

(transcript below)

A couple months ago, my son joined me in listening to Elvis

Presley -- his Sun Sessions recording to be exact. Corey took to liking it.

Excited about this, I sort of gave a history lesson on Elvis in a way a 5

year-old could understand. I showed him pictures of Elvis on the web and even

showed the young Elvis performing Jailhouse Rock. He asks me a question that he

asks whenever talking about someone from the past. It is a question that arose

after his grandfather died when he was just 4. Is he in heaven? It’s Corey’s

way of asking if someone is dead.

At first, I chuckled a bit, thinking about the cultural joke

that Elvis is alive and living on earth somewhere. Then I got serious. I answered truthfully.

Yes, Elvis is in heaven. Corey became upset at this, having taken a liking to

Elvis rather quickly. “No, he is not in heaven! No, he is still here, right

Daddy?!” I tried to assuage him with the notion that because his music is still

with us, he is still with us, and thus he lives in a way. But of course, a five

year-old, Corey has some difficulty with the abstractness of this. But I think

he got the essence of what I was saying, or at least, he stopped crying and

went on to the next thing.

Yet thinking about it, the notion of the innate need for

Easter came to mind. We all want to see those we love again. Most cannot fathom

that this life is the end. We desire a resurrection so that reunions with those

we’ve lost and deeply miss are possible. We want to see loved ones in heaven

again. We want to see Elvis again. This would especially be the case if we lost

his music.

There is an emotional need behind the story of Jesus coming

back after his disciples and friends thought he was gone.

Easter is a sacred metaphor of, when we need it most, experiencing

a way arising out of no way.

The Easter story, the original Easter story, points to the

basic paradigm of loving, losing, grieving and somehow finding wholeness in

spite of the despair. The relationship between Jesus and his disciples points

to this.

That relationship was more than just a teacher-student

relationship. Jesus called his disciples friends. They were friends walking the

dusty trails of Palestine together, eating together, learning together, serving

the community together. The bond was real and profound.

As for the disciples, they often called him, Lord, or in

modern lingo, “my greatest friend and beloved mentor.”

So imagine in the tragic end having to flee your greatest

friend and beloved mentor at his darkest moment. This is what the disciples had

to do. It would be the equivalent of a soldier leaving his commander, his

comrade, alone in the heat of the battle, leaving him to die. The guilt cannot

be underestimated.

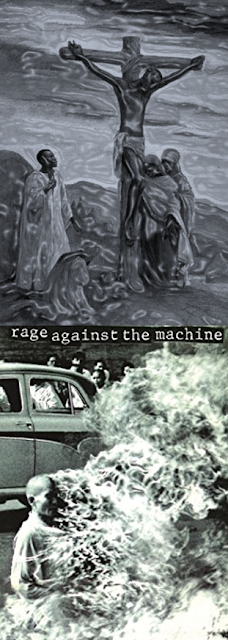

You may ask, why did the disciples have to flee? My

understanding of Jesus’ death is that instead of leading his ragtag band of

brothers in militant revolution against the Roman Empire, Jesus chose instead

to save his friends lives by giving himself up, an act of peaceful resistance

that led to his crucifixion. It is the equivalent of Tibetan monks sacrificing

themselves to resist China’s occupation and cultural genocide. Jesus knew the

significance and meaning of his self-sacrifice would lead to transformation in

his friends and maybe, hopefully, in the hearts and minds of the Jewish people

suffering under the weight and power of the Roman government. Jesus was hoping

for the ancient Jewish equivalent of the Arab Spring.

And so it was necessary that Jesus’ disciples flee the scene

so as not to be gathered, arrested, and possibly executed themselves. Even

Peter who swore to himself and to Jesus that he would never leave his teacher’s

side, left. Jesus knew this would happen, and needed it to happen for his

teaching to be continued after his departure from the scene. Jesus dying

without his friends close by was necessary, for the disciples would have been

next.

Still, the grief the disciples felt in the aftermath was

wrenching. That grief was compounded by the unbearable heaviness of guilt.

If this guilt was not assuaged, who knows what the lives of

the disciples would have amounted to.

But Jesus’ spiritual return – yes, I believe it was spiritual not

physical – comforted and saved his friends from the turmoil of loss and guilt.

This is what we call the resurrection: Jesus’ returning to comfort and salve

the hearts of those grieving and guilt-laden. And it was indeed transformative

and eventually led to the Pentecost, to the beginning of the church, yes, as it

went, even this church.

We should not be surprised by Jesus’ return to the hearts

and minds of those who loved him so much. Visions and visits from loved-ones

who’ve transmigrated to God’s love and yet who return to us in spirit -- this

is a human phenomenon.

A 2008 article in the Scientific American called “Ghost

Stories: Visits from the Deceased” discusses the very common occasion of

grieving loved-ones receiving visits from the loved-one who has passed. The

article cites how in one study, 80% of elderly people experienced visions of

their dead partner one month after bereavement.” 80%!

Last month, in a meeting of our Men’s Breakfast Bereavement

group, I talked with a man who lost his wife of some 50+ years a few months

ago. He is a highly educated, urbane, and intelligent guy, in fact a professor at

the local community college. He shared with me in discussing his grief how he

senses his wife’s presence with him regularly. Though he qualified it, he said

I even talk to her sometimes. It provides him a sense of comfort. Knowing she

remains with him in some way softens the powerful gusts of grief. Now, those

not in the hospice bu’ness might say this guy is off his rocker. But knowing

how normal and common this is, I made clear to him that this is not at all

unusual. We hear stories like this all

the time.

Such experiences of spiritual resurrection, if you will, of

sensing life despite loss, help us to face the reality of loss. These

experiences help us to persevere through the brutal reality that things change,

we lose what we love, the comfortable normal changes into the painful abnormal.

And as is true with the grieving process, whether it be

grief over losing a loved-one or in losing our comfortable norm, from the fire

of loss eventually comes the growth of a new forest. Yes, scars of that fire

remain, but the soil is stronger, more resilient, more enduring. SO the fire of

loss that is the crucifixion gives way to the seedling of new life in spite of

loss -- this is the resurrection. And the resurrection in turn gives way to the

new forest that is the Pentecost.

I think again of Elvis. To me, Elvis is at his artistic best

when he is singing the Blues that he learned in the Black clubs and dancehalls

of Memphis or when he is singing the spiritual music he learned in church, both

his own and the Black church he would sometimes visit to hear Black gospel.

As Elvis discovered, the power and joy of the music comes

from its life-giving way amid the life-denying realities all around. In the case of African-Americans, the

life-denying realities of slavery, Jim Crow, and racism. Black spirituals and

the blues, in other words, are a simile for the Easter story.

James Cone, a former professor of mine at Union Theological

Seminary, wrote a great book called The Spirituals and the Blues. In this book

he interprets the connection between Black Spiritual music and the Blues,

saying Spirituals pointed to eternal hope beyond despair while the Blues

pointed to the temporal hope found in being honest about despair. Both point to the subversive statement that

circumstances around us may say no way, but our spirits, fueled into music and

fueled by music, says, “yes, way.” In spirituals and the blues we have a

representation of being honest about despair and death, yet in the process

defying the external reality with an internal reality filled with the hope of

life, with new life embodied in the resurrection and continued in the

pentecost.

Dr. Cone puts it like this:

“Herein lies the meaning of the resurrection. It means that

the cross was not the end of God's drama of salvation. Death does not have

the last word. Through Jesus' death, God has conquered death's power over his

people…. The resurrection is the divine guarantee that black people's lives are

in the hands of the Conqueror of death… They don't have to cry anymore.”

I still recall the broken carillon bells of New York City’s

Riverside Church. Riverside Church is right next to Union Theological Seminary

and its building of apartments called McGiffert Hall. I’d just moved in to

McGiffert and would begin seminary in a few days. My apartment loomed in the

shadows of Riverside’s huge, beautiful steeple, something I admired right away.

My first class at Union was to begin on the 11th of that month… of September. Yes, in 2001. 9/11. Needless to say, the class was canceled.

Two commercial planes hit the two towers and life changed. It reappeared broken.

The huge, beautiful steeple of Riverside, whose carillon bells were silent while being refurbished that year, seemed a little less beautiful and admirable. Reaching to the heavens, it seemed an easy target. So did the Jewish Theological Seminary right across the street from Union. In those first couple weeks after 9/11, I would wake many nights upon the sound of planes overhead. The sound of protection from military planes and the sound of attacking from terrorist planes would sound rather similar and thus hard to differentiate, so I thought.

Through the Fall and Winter, the carillon bells of Riverside Church continued to stand silent. Broken bells cannot sing. And this was fine with me. For months after 9/11, I could not listen to music. Music, which had always been a source of healing and joy, which was such an indelible part of my life -- I could not bear to hear it. Music seemed too easy, too entertaining, too ideal. There seemed to be no note or musical phrase that could make any sense of it all or condone the escape. To listen to music would merely be a naïve anesthetic away from reality. That’s the kind of effect 9/11 had. It was a long, long winter.

But then came Spring. Then came Easter.

The Easter morning of 2002 for me began with quiet. I was not up to the show of Easter at church. I had been skipping church for weeks. Going to an Easter service seemed too easy a penance.

The morning itself would become my Easter service.

The morning ritual of making coffee was the prelude. The gurgling and dripping of the coffee maker served as preparation for sounds to come. The coffee and I ready, I prepared the day's first cup of coffee as if the invocation. Each sip became a little prayer. Each moment in between, a meditation.

Then the re-born bells of Riverside Church sounded. They filled the morning air with an ecstatic flourish. There seemed not rime or reason to the music, just sound sounding and pervading. It scared me at first. But then I simply listened and smiled. The heavenly sound echoed all along Claremont and Broadway and through the whole of Morningside Heights. It pierced my heart. And as the vibrations of sound gave way to vibrations of sound, I cried like a child, completely vulnerable yet completely embraced.

On that same sunny, crisp, church-less Sunday morning, I opened the CD player’s dusty door. Inside, secure and replete with possibilities, was U2’s All That You Can’t Leave Behind. It survived throught the winter and was opened to a new day. I hit play. The first track, “Beautiful Day,” sang. It begins with the words,

“The heart is a bloom

Shoots up through the stony ground…”

Playing on the finale of the Noah and the Ark story, you

know, where the dove comes back to mark the end of a nightmare and reveal the

promise of grace, represented by a rainbow’s beckoning:

“And see the bird with a leaf in her mouth

After the flood all the colors came out…

After the flood all the colors came out…

It’s a beautiful day”

It is Easter morning some 11 years later. Easter, as always,

represents the process of escaping the mire of our old lives and realizing the

light of new life. And it is especially poignant when contemplating the despair

of grief, of losing what we once held close. This is the story of the original

Easter, and of every one before and since.

A spiritual Elvis loved to sing is actually a new spiritual

written by Tommy Dorsey for the famed gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. It

incorporates themes from the 23rd Psalm and is called “Peace in the Valley. ”

It speaks to the Easter message of hope rising out of despair, peace found

despite the valley of the shadow of death, and a Presence of Light and Love

leading us to a new life of green pastures, still waters, right paths.

I will end by offering a lyric from this new spiritual, and

let it serve as our Easter prayer.

There the flow'rs will be blooming, the grass will be green

And the skies will be clear and serene

The sun ever shines, giving one endless beam

And the clouds there will never be seen

And the skies will be clear and serene

The sun ever shines, giving one endless beam

And the clouds there will never be seen

There the bear will be gentle, the wolf will be tame

And the lion will lay down by the lamb

The beasts from the wild will be led by a Child

I'll be changed from the creature I am

And the lion will lay down by the lamb

The beasts from the wild will be led by a Child

I'll be changed from the creature I am

Comments

Post a Comment