The Black Spiritual Tradition, Jesus & Freedom

During his

chapel messages, he’d often lead the students in an acapella singing of a Black

Spiritual.

Amazingly,

I was able to find online an example of a Cedarville College chapel service led

by Paul Dixon where we sang that spiritual. This is from March 30, 1992:

Holly and I were there! It’s kind of neat to think that among those voices singing that Spiritual some 30 years ago were Holly and my voices. Hers was much better, of course.

That chapel

rendition is good, I’d say. But it lacks a certain spirit that comes with Spiritual

tradition. Here’s what I mean…

There’s a danger in us singing Black Spirituals that I don’t think we should ignore.

Without an

understanding of the significance of Black Spirituals, we don’t do the music justice.

We really need an understanding of where

the music came from and what it signified. I’d like to do my best here to help

us understand. And through this understanding, it is my prayer that a deeper

faith is moved in us.

The Black

Spiritual was the earliest example of African American music forged on this

continent, and it set the stage for African American music from then on. That

said, we should remember this - the enslaved Africans brought here against their

will arrived with their own culture of music. Indigenous African music was sung

on slave ships, sung to somehow survive the brutalization and torment.

The earliest

music African expressed on this continent was forged in Africa and

brought over. And eventually, the enslaved, despite their plight, forged a new

music, adapting Christian stories and fusing them with African sounds. This new

music – the Spiritual - is what we discuss and sing this morning.

Enslaved

people adapted Christian stories and music. This fact is important to consider. We might

have the idea that enslaver missionaries preached their white Christianity to

the enslaved, and the enslaved simply took that tradition at face value

initially, and that it morphed over time to become what it is now. That is a misreading

of the history.

Historian Henry

H. Mitchell in his book, Black Church Beginnings, writes, the enslaved people’s

“adaptations of Christianity is due very largely to [their] own initiative, not

to missionary labor for the most part.”

In other words,

the enslaved didn’t simply take in the Christianity of their enslavers. No,

they held it up, cross-examined it, and eventually created their own slant

on Christianity, one infused with a truer light, a freer light. They in some

sense transfigured the Christianity they were handed.

They highlighted the Exodus story of Moses and the Israelites, a story of chains gone, the Pharoah’s army drowned, and the year of jubilee known. In that Exodus story, they saw themselves.

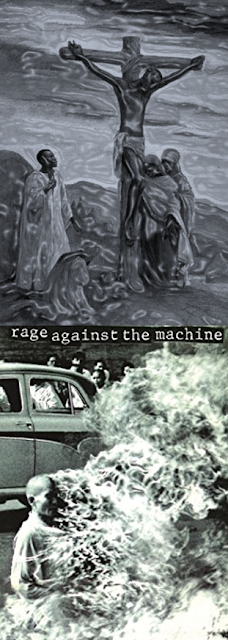

They highlighted the human Jesus, the one rejected and despised, the one of constant sorrows, the one whipped and tormented and hung on a tree, yet the one whom death could not keep down.

In Jesus, they saw themselves.

They highlighted the early church, snd figures like Paul and Silas who were beaten down and persecuted, placed in chains, and imprisoned by the powers that be. In the early church, they saw their own plight, and believed the chains would come off, the prison doors would be tossed open, and freedom would be felt one day.

See, the enslaved internalized the biblical stories, Jesus and the early church, along with Christian hymns, and they adapted all of it to their own understanding, experiences, and worldviews. From the very beginning, there was transfiguration going on – European Christianity, with its condoning of slavery, that handed down to them; but Black Christianity, with its subversive call for freedom and its focus on justice and hope despite despair, that's what was recreated on the other end.

And, yes, if

we look with open eyes, we see Black Christianity’s subversiveness in the Spirituals.

Black Liberation

Theology icon, James Cone, in his powerful book The Spirituals and the Blues

discusses this subversiveness. I’d like to quote from this text at length…

“It is the

spirituals that show us the essence of black religion, that is, the experience

of trying to be free in the midst of a "powerful lot of

tribulation."

Oh Freedom! Oh Freedom!

Oh Freedom, I love thee!

And before I'll be a slave,

I'll be buried in -my grave,

And go home to my Lord and be free.

The spirituals are songs about black souls, "stretching out into the outskirts

of God's eternity" and affirming that divine reality which lets you know

that you are a human being—no matter what white people say. Through the song,

black people were able to affirm that Spirit who was continuous with their

existence as free beings; and they created a new style of religious worship.

They shouted and they prayed; they preached and they sang, because they had

found something. They encountered a new reality; a new God not enshrined in

white churches and religious gatherings. And all along, white folk thought

the slaves were contented, waiting for the next world. But in reality they were

"stretching out" on God's Word, affirming a new-found experience that

could not be destroyed by the masters. This is why they could sing:

Don't be weary, traveler,

Come along home, come home.

Don't be weary, traveler,

Come along home, come home.

My head is wet with the midnight dew,

Come along home, come home.

The mornin' star was a witness too,

Come along home, come home.

Keep a-goin', traveler,

Come along home, come home.

Keep a-singin' all the way,

Come along home, come home.

Jes' where to go I did not know,

Come along home, come home.

A trav'lin' long and a trav'lin' slow,

Come along home, come home.

In the spirituals, black slaves combined the memory of their fathers [and mothers] with the Christian gospel and created a style of existence that participated in their liberation from earthly bondage." (James H. Cone. The Spirituals and the Blues . Orbis Books. Kindle Edition.)

As I wind things down, I go back to Cedarville College and to that Spiritual I began with. By the time I sang in that chapel service in March of 1992 with Holly singing somewhere in that space along with me, I had heard a reworking of that same Spiritual, "Woke Up this Morning." Earlier that year, around Dr. King day in January, I decided to study Dr. King’s work and the Civil Rights Movement. This wasn’t part of any class, just my own curiosity and eagerness to learn. Part of that self-study was a viewing of the landmark documentary, Eyes on the Prize. In that 14 part series, a song appeared regularly. It went something like this:

From Jesus to Freedom. You might think it a big change. But not really. The Black Spiritual tradition makes it clear that Jesus and Freedom go together. In some sense, Jesus and Freedom are interchangeable. Jesus, after all, is the liberator, and not just spiritually.

That Jesus and Freedom go together, this is a truth white American Christians need to hear. We can’t preach Jesus on Sunday and then Monday through Saturday ignore the reality that Black Americans don’t experience the freedoms we do.

Here’s just one example – the freedom of invisibility. I go into a supermarket, and I do not worry about being noticed, stared at, worried about, or even followed around. I am in some ways invisible as a white person in most aspects of American life. No one pays me mind.

Ask most Black Americans, and they will

tell you, this freedom of invisibility in white America is not a thing for

them. People pay them mind. They are not free from that. And that is

exhausting! Living in South Korea, and being noticed everywhere I went, I can

attest to how exhausting this is.

Here's another

– economic freedom is a freedom still not experienced by most Black Americans.

The disparity between white and Black Americans when it comes to economic

security remains a sinful reality.

Following Jesus means following Jesus in the work of liberation, the work of lifting up the oppressed and the unfree, and continually confronting inequity.

So, as we continue singing Spirituals this morning, let us stand in solidarity with our Black brothers, sisters, and siblings for whom those Spirituals mean everything. In this time of whitewashing our difficult history, let us feel and internalize the pain and sorrow and hope out of despair heard in these powerful songs. As we acknowledge the genius and the power of this music and of the people who moved this music, let us join in the struggle to make all people free, especially those whose fore-parents knew the ravages of human bondage. As we close out this month devoted to Black history, may Jesus the liberator free us here of racism and racial hatred and bias, and may we see the creation of a better history going forward, a history beginning now where "justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream."

Comments

Post a Comment